The Origins of Matcha: How a Ritual Became a Global Ingredient

Matcha is often viewed today as a modern superfood or café staple, but its origins trace back over a thousand years. Understanding how matcha developed from a medicinal preparation to a refined cultural practice helps explain why it continues to hold such value in today’s global food and beverage industry.

Early Roots in Tang and Song Dynasty China

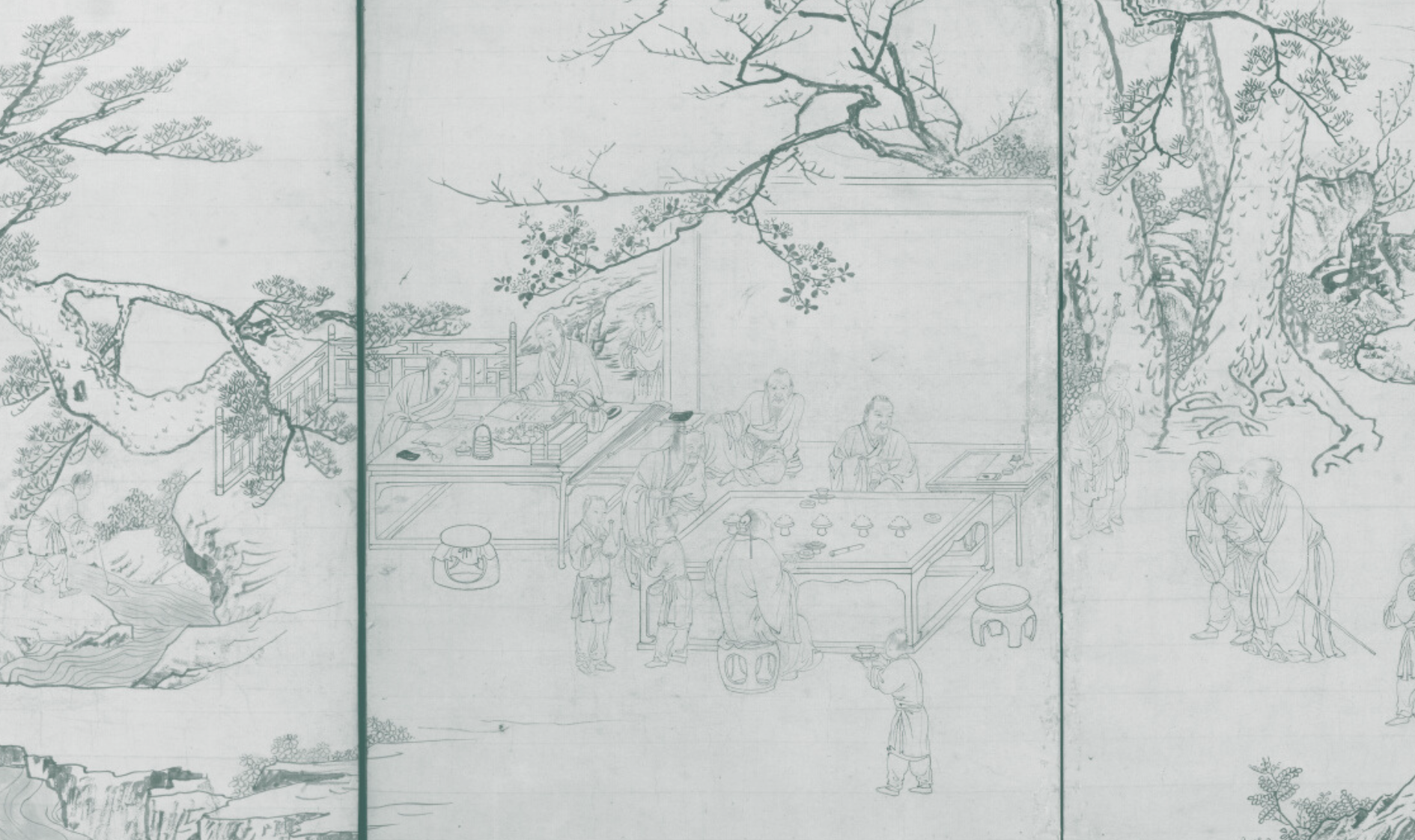

The foundations of matcha were first established in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), when tea leaves were steamed, compressed into bricks, and prepared by grinding into powder before being whisked with hot water. This powdered tea method evolved further during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), where whisked powdered tea became a formalized and respected practice among scholars and monks.

At this stage, powdered tea was valued for its:

- Concentrated flavor

- Energizing effects

- Ease of preparation for meditation and study

These early techniques laid the groundwork for what we now recognize as matcha.

Transmission to Japan and Monastic Adoption

In the late 12th century, Zen Buddhist monk Eisai introduced powdered tea seeds and preparation methods to Japan after studying in China. Tea quickly became integrated into Zen monastic life, prized for its ability to promote calm focus during extended meditation.

Japanese monks refined the cultivation process by:

- Growing tea plants in carefully managed environments

- Selecting specific cultivars for powdered tea

- Emphasizing freshness and preparation precision

Over time, these refinements distinguished Japanese matcha from its Chinese predecessors.

Matcha and the Samurai Class

From the Kamakura period onward, matcha was also widely embraced by the samurai class, who were deeply influenced by Zen Buddhism. Samurai valued matcha for its ability to promote calm focus, mental clarity, and sustained alertness, making it well suited to both meditation and martial discipline.

Beyond its functional benefits, high-quality matcha and tea utensils became symbols of status and refinement among warrior elites. Samurai patronage helped elevate matcha from a monastic practice to a broader cultural institution, playing a key role in its establishment within Japanese society.

The Development of Tencha and Shaded Cultivation

One of Japan’s most significant contributions to matcha was the development of tencha, the raw material used exclusively for matcha production. Unlike sencha or other green teas, tencha leaves are:

- Shade-grown for several weeks before harvest

- De-stemmed and de-veined after steaming

- Stone-milled into a fine powder

Shading increases chlorophyll levels and amino acid content, creating matcha’s signature vibrant green color and umami-forward profile. This agricultural innovation firmly established matcha as a distinct tea category.

Formalization Through the Japanese Tea Ceremony

By the 15th and 16th centuries, matcha became central to the Japanese tea ceremony (chanoyu), particularly through the influence of tea master Sen no Rikyū. The ceremony emphasized:

- Simplicity and mindfulness

- Precision and consistency

- Respect for craftsmanship and ingredients

This ritualized use of matcha helped preserve strict quality standards and elevated powdered tea from a functional beverage to a cultural symbol.

Transition From Ritual to Commercial Production

For centuries, matcha remained largely ceremonial and regionally consumed. However, industrialization in the 20th century enabled:

- Mechanized shading systems

- Improved milling technologies

- Expanded cultivation beyond traditional regions

These advances allowed matcha to move from a niche ceremonial product to a commercially viable ingredient, suitable for food manufacturing and global distribution.

Matcha in the Modern Global Market

Today, matcha is sourced and produced across multiple countries, each contributing to its evolution. While Japan remains the benchmark for traditional and ceremonial-grade matcha, other producing regions (including China) have adapted the foundational techniques to meet modern market demands.

In contemporary B2B supply chains, matcha is valued not only for heritage, but also for:

- Functional performance

- Flavor consistency

- Scalability

- Application-specific suitability

Conclusion: A Legacy That Enables Innovation

Matcha’s journey, from ancient Chinese monasteries to modern global manufacturing, illustrates its adaptability and enduring relevance. What began as a meditative aid has become a versatile ingredient powering innovation across cafés, beverages, confectionery, and functional nutrition.

For B2B buyers, understanding matcha’s origins provides context for today’s sourcing decisions: respecting tradition while embracing modern production and diversified supply.

We are available to give you the best advise on the best matcha for your company's industry

.png)

.avif)